Who are the 15 figures?

Throughout my enquiries about the painting there has been almost continuous disagreement as to the identification of the 15 figures. In this section of the website I try to produce evidence to support the catalogue's identifications.

One expert wrote that he was not sure who any of the figures were. He saw no reason to identify the figure with both feet in the octagon as Francis I, who was always depicted with a long face, long nose and thin beard. The man in red looked even less like Charles V, and was not dressed in rich enough costume to make one think he was an emperor. The idea that any painter would have represented the Holy Roman Emperor standing so close to the King of France and poking him in the chest with his finger is most unconvincing: Royal figures were always depicted in a decorous and respectful way in the art of the time.

In the face of such scepticism I resorted to trying to demonstrate identifications by comparing the painting's 15 figures individually with contemporary prints or paintings. This has been made more difficult because the quality of some of the painting is very uneven.

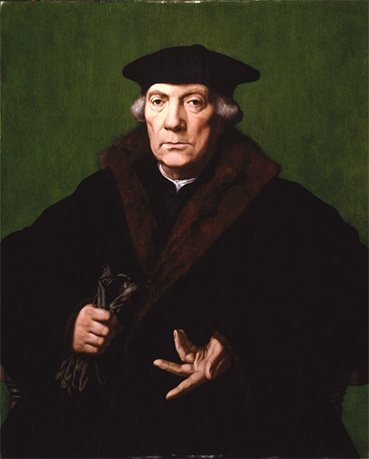

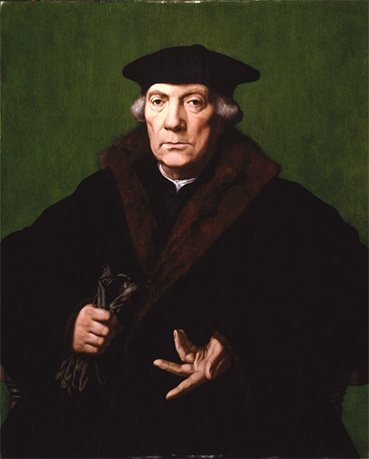

Charles V

Charles V was painted many times. Practically all the portraits featured his elongated Hapsburg chin which is strikingly evident in these two examples.

Many experts have supported the Ghent catalogue's identification and it is interesting that no one during the exhibition challenged it. But there has also been a minority who have strongly argued that it is not Charles V despite accepting the Hapsburg chin. They say how could the most important man of his day be painted almost facing backwards.

Charles and Francis I at whom Charles is pointing met more than once in their lives but not at Cambrai in 1529. How then can one explain the fact that the painting shows them together. The Ghent catalogue dealt with this difficulty by saying it was an allegorical painting. But then the painting is not a strict allegory, more a fictionalised representation of an historical event.

Francis I

Francis I was also painted many times and two such paintings are shown here.

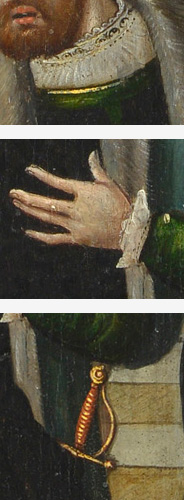

Many who have viewed the painting agree that it is meant to be Francis I. But there has been a lively minority who question that identification. Where for instance are the decorations that he used to wear round his neck. So I took a photo of the painting to a dress expert in the V&A and her comments were quite enlightening. First Francis was wearing a court bonnet with jewels in it, quite unusual. Second he had on a shirt with a gold embroidered collar, almost certainly a sign of royalty Third his cuffs were trimmed with gold. Fourth he had silver clips on his wrists to hold his cuffs and fifth the pommel of his sword was gilded... All added up to saying that he was a royal personage.

The 3 Ladies

Quite unusually for a painting of such age there are three women in the foreground. What are they doing there? The answer is that two of them had been negotiating the Peace of Cambrai, Louise of Savoy mother of Francis and Marguerite of Austria sister of Charles V. There is doubt about the identity of the third lady. Some think it is Eleanor of Portugal, widow of the King of Portugal and destined to marry Francis I. Others believe it must be Marguerite of Navarre the daughter of Louise of Savoy because in contemporary accounts of the peace negotiations and thanksgiving service in Cambrai Cathedral, the third lady is identified as Marguerite. Many people find it hard to understand why the reconcilers are so poorly painted when other figures are clearly attempted portraits. Finally the precedence of the women is questioned? Shouldn't Louise be in front?

The Bourgognes

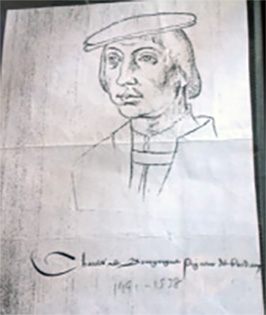

I had some difficulty in identifying the two figures behind Charles and Francis. It wasn't until I chanced on the Receuil d'Arras in the Victoria and Albert art library that their identities could be established. They were among portraits by Jacques Leboucq of many eminent and interesting people who were living in France in the early 16th century.

Why are they in the painting? The only clue that I found was in a book published in Geneva in 1548 by Jean Calvin which claimed that they were childhood friends of Charles. Then there is a wildly obscure footnote in a reference book by A.Dek saying that Charles Bourgogne had undertaken a special mission for the Emperor to a court of Arbitration in Cracow. Further research has proved fruitless.

The Best Portrait

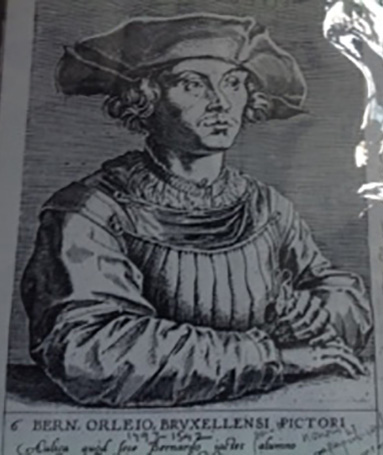

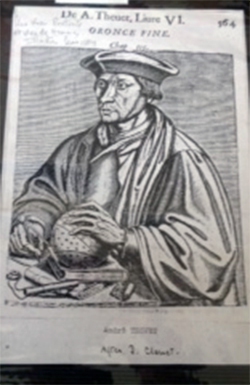

The best portrait in the painting is that of the character next to the right hand pillar with one hand on the ledge. Early on I identified him as Oronce Fine, a mathematical professor but somebody pointed out that mathematical professors did not wear red berets. Then I found a print of Barend van Orley.

This was the best identification yet. He was also mentioned in the Sotheby's 1979 sale of the painting which was attributed to 'circle of Barend van Orley'. He is painted in the position that artists putting themselves in their own painting are said to favour. In Sotheby's opinion the painting is not by him although he was at one time Marguerite of Austria's court painter. It is quite possible that it was painted by members of his studio or apprentices who were recording an important event at somebody's request. Occasionally other members of the studio more specialised or skilled might contribute to the painting. It is likely that whoever painted the pillars did not paint the background rocks or the scroll.

Bishop Carondolet and The Dauphin Francis

Turning now to the two figures in the left-hand arch. Who are they? The hand on the shoulder could indicate a warning or be avuncular. It was only after I had had the painting cleaned that the gold embroidered right-hand sleeve of the younger character was revealed. Was it possible that the artist was trying to show Francis I's younger son,also called Francis who had been imprisoned in Spain to allow his father's release? In which case it is likely that the figure stretching out his hand is Bishop Carondolet who had been Charles' Secretary for many years. Behind them in what looks like the arch of a ruined church is a pikeman walking across the arch. Might he be meant to symbolise the imprisonment of the young Francis in Spain?

Bishop Carondolet or Chancellor Duprat

The commentary describing the painting in the catalogue for the quincentenary Charles V exhibition identifies the cleric in black as Bishop Carondolet. But a contemporary account La Triumphe de la Paix Celebree en Cambray 1529 by J.Thibault describing the peace negotiations and the service in Cambrai cathedral a few days later, identifies the cleric differently as Chancellor Duprat Cardinal Archbishop of Sens and Chancellor of France who was Louise of Savoy's Chief Minister during the captivity of Francis I in Spain.

Whoever it is the underdrawings (of which more later) reveal that the artist first of all drew the cleric's head slightly downwards but in the finished painting the head has been raised and the bishop's countenance made to look stern and directly at the disputants. It is possible that the cleric commissioned the painting and disliked the first attempt at portraying himself.

Just under the scroll there dangles a seal, oblate in shape and black in outline with a red Crozier painted inside it. Seals, of course authenticate the documents such as Treaties or marriages to which they are attached and oblate seals signify that they either belong to a lady or come from a religious source- in this case perhaps conveniently both. The Crozier denotes a bishop and strengthens the identification of Carondolet. But I was firmly told by one expert that it was ridiculous to suggest that a peace treaty would be identified by such a pathetic looking scroll.

The Obscured figures

Of the 15 people in the painting two are difficult to see and identify because their faces are not fully painted. One wearing a red hat is just beneath the left-hand pillar and sandwiched between the two heads in front of him. The other, slightly more visible, is standing against the right-hand pillar with a slanted red hat and sporting a curly moustache.

I wondered if their faces were fully painted would they be more recognizable. Fortunately I knew someone who specialised in quick drawings of people and asked him to imagine their full faces and see what he could do. The result is shown here.

I have shown the drawings of these obscured faces to a number of people in the hope that they might be identified but so far no luck.

» Go to next section: Who painted the painting? (The Painter)

Bishop Erard de la Marck

Quite why some figures are 'outside' the immediate action and apparently not very interested in it I can't explain but I found several other contemporary paintings that used that approach. The four figures in the right hand arch are identifiable as clearly the artist/s intended they should be. With no other lead I studied a large number of photographs of 16th century paintings in the Witt collection in London. Amongst them I chanced on someone who seemed like the character with a triangular hat. His name was Bishop Erard de la Marck.

He was the Prince Bishop of Liege from 1506 to 1538 and was made a cardinal in 1520. He had allied himself with Charles V and is recorded in contemporary accounts of the Peace of Cambrai as being present at that event.

Anne de Montmorency

Another difficult identification is the character to the right of Bishop Marck. It is possible that he is Anne de Montmorency, Marshall and Constable of France. He was a soldier statesman and diplomat in the service of Francis I with whom he shared captivity in Spain. Later he helped negotiate the Peace of Cambrai at which he was present.

Please submit your comments below...

© 2021-22 · Website created Summer 2016. All paintings and illustrations owned by their respective authors and factual inaccuracies the sole responsibility of the website owner.

View sitemap · Web Design by Dream Digital