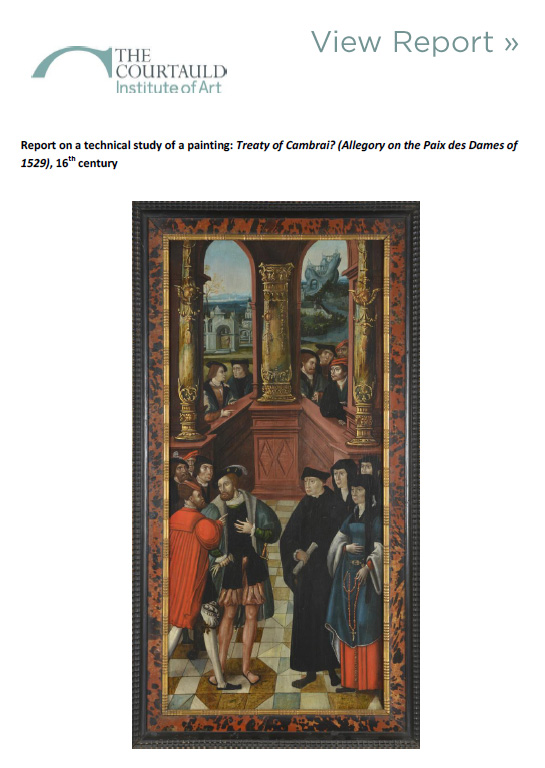

Who are the 15 figures?

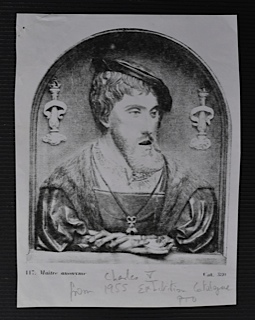

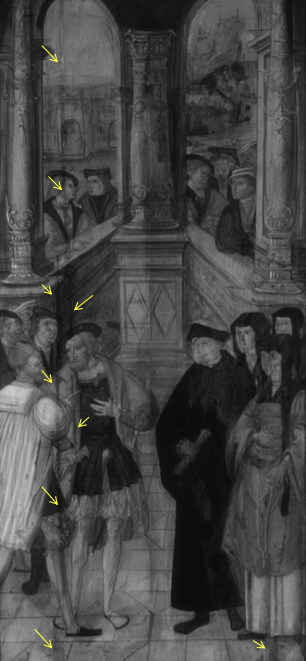

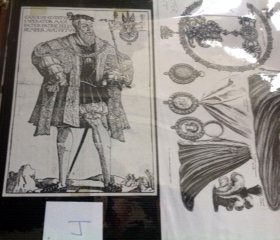

Charles V

Throughout my enquiries about the painting there has been almost continuous disagreement as to the identification of the 15. In this section of the website I try to demonstrate identifications by comparing the painting's 15 individually with contemporary prints or paintings.

One expert wrote that he was not sure who any of the figures were. He saw no reason to identify the figure with both feet in the octagon as Francis I, who was always depicted with a long face, long nose and thin beard. The man in red looked even less like Charles V, and was not dressed in rich enough costume to make one think he was an emperor. The idea that any painter would have represented the Holy Roman Emperor standing so close to the King of France and poking him in the chest with his finger is most unconvincing: Royal figures were always depicted in a decorous and respectful way in the art of the time.

In the face of such scepticism I resorted to trying to demonstrate identifications by comparing.

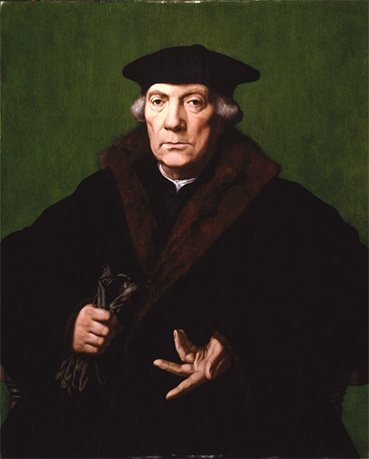

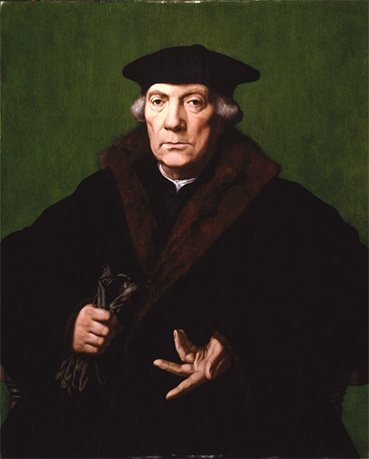

Charles V was painted many times. Practically all the portraits featured his elongated Hapsburg chin which is strikingly evident in these two examples.

Many experts have supported the Ghent catalogue's identification and it is interesting that no one during the exhibition challenged it. But there has also been a minority who have strongly argued that it is not Charles V despite accepting the elongated chin. They say how could the most important man of his day be painted almost facing backwards.

Charles and Francis I at whom Charles is pointing met more than once in their lives but not at Cambrai in 1529. How then can one explain the fact that the painting shows them together. The Ghent catalogue dealt with this difficulty by saying it was an allegorical painting. But then the painting is not a strict allegory.

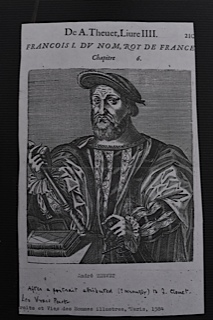

Francis I

Francis I was also painted many times and two such paintings are shown here.

Like Charles many who have viewed The Painting agree that it is meant to be Francis. But there has been a lively minority who question that identification. Where for instance are the decorations that he used to wear round his neck. So I took a photo of the painting to a dress expert in the V&A and her comments were quite enlightening. First Francis was wearing a court bonnet with jewels in it, quite unusual. Second he had on a shirt with a gold embroidered collar, almost certainly a sign of royalty Third his cuffs were trimmed with gold. Fourth he had silver clips on his wrists to hold his cuffs and fifth the pommel of his sword was gilded... All added up to saying that he was a royal personage.

But the doubters were not moved so I asked one of them what evidence would you accept as proving that the painting is indeed The Peace of Cambrai with the figures identified as they are. He replied. First there could be a letter written at the time which referred to the painting. Second there may have been a contemporary article written about the painting. Third someone knows where the painting has been between 1530 and 1934 when it was sold by an auction firm called Lepke in Berlin and lastly somebody else knows that the painting has been part of a storyboard with several similar panels alongside it. Any of these could be accepted as settling the issue.

The 3 Ladies

Quite unusually for a painting of such age there are three women in the foreground. What are they doing there? The answer is that two of them had been negotiating the Peace of Cambrai, Louise of Savoy mother of Francis and Marguerite of Austria sister of Charles V. There is doubt about the identity of the third lady. Some think it is Eleanor of Portugal, widow of the King of Portugal and destined to marry Francis I. Others believe it must be Marguerite of Navarre the daughter of Louise of Savoy because in contemporary accounts of the peace negotiations and thanksgiving service in Cambrai Cathedral, the third lady is identified as Marguerite. Many people find it hard to understand why the reconcilers are so poorly painted when other figures are clearly attempted portraits. Finally the precedence of the women is questioned? Shouldn't Louise be in front?

The Glued Stamps

Glued to the back of the panel as well as the catalogue fragment were two similar stamps.

They appeared to record a date 1/26 but I didn't think that was the whole story so I sent one of the stamps to an expert that I knew and he replied 'your stamp is not an official customs stamp for collection of revenue but a perforated label suitable for writing reference numbers et cetera and an early form of self adhesive label. The label is made of wood pulp paper typical of the period 1880 to 1930 and the inscription is probably in aniline ink mainly used from 1890 onwards. Both labels bear the same inscription. The figures could be a date or reference number of a customs official or department. The form of cross shown is used on Swiss post age and revenue stamps from 1850 onwards. my guess is therefore that your painting passed through a northern Swiss Customs Office in January 1926.

I didn't think this was the whole story so I then approached the Swiss Customs Office to ask about the stamps. They replied that they couldn't actually find anything in the customs archives and referred me to the Swiss National Museum.

The museum then carried out its research including asking an 86 year old customs officer what he thought the answer was. He replied "that the stamp is a 'Geubuhren-Oder Taxmarke' used by the federal customs administration of Switzerland but also used in Germany or Austria. It was stamped before 1930. Your stamp was stamped in Switzerland, in (Zollkreis 1) Basel in one of the many Customs Offices in this area (Zollstelle number 26). The 1/26 is therefore nothing to do with a date but to do with customs administration. The answer regarding why two stamps was either that the painting crossed the border twice (perhaps to the auction and back) or each stamp had a value so it could be that the worth of the painting needed two stamps or more. Finally it became evident that there were no customs records available because they were destroyed after 5 years."

So the hope that the stamps might lead to some identification of the picture's owner/s fizzled out but they did indicate that the painting had crossed the Swiss border some time before 1930.

Cut

Where has the Painting been Since the Early 16th Century?

The Transfer and the Central Pillar

Soon after buying the painting I noticed that it was painted on a thick support both the thickness and type of wood being unusual for a painting of that age. On examining the top edge I saw that the support was made up of different pieces of wood glued, together.

To obtain a more knowledgeable view I decided to take the painting to the National Gallery and show it to their chief restorer. He said that it was obvious that the painting had at some date been transferred-transfer being the process by which a painting on panel/s may have become fragile and needed to be transferred to a more solid support in order to secure it. It was impossible to say when this was done the technique being used for about 200 years and there was no way by which the actual people who had done it could be traced.

It was possible that during the transfer some damage was done and that might have been responsible for the artificial nature of the middle pillar which is broader than the other two and its right-hand side being a poor copy of its left Indeed several observers have commented that it might have been two panels joined together.

It wasn't until 2014 that I sought the advice of Oxfords Dendrochronology laboratory and an expert came to look at the painting. His views were -

1. The support was made up of a piece of Blockboard on which had been glued a piece of pine about a sixteenth of an inch thick on which in turn the painting had been glued apparently without grounds. It was an incredibly skilful piece of work.

2. There were three pieces of thin panel originally with the first join 10.16cm from the left-hand edge. The second was 17.78cm further to the right and the third another seven to the right hand edge making a total of 45.72cm altogether.

3. The measurements of 10.16cm, 17.78cm and 17.78cm inches strongly suggested that the original width of the panels used must have been 53.34cm. The 10.16cm piece had for some reason been cut along its left-hand edge and in so doing chopped off part of Charles V's cloak and body. There could be no certainty why this had been done. It might have been damage during the transfer, or the need to fit in a frame or be part of a storyboard.

4. There was also a further join down the middle of the central pillar.

Down the years there have been many comments about the fact that the middle pillar is broader than the other two. The photo of the three columns and their underdrawing confirm the join down the middle column.

The fact that the quality of the painting-cleric's hand and scroll is so poor indicates that another hand must have been at work possibly to repair damage during the transfer by re-imagining a broader column with the right extension being an attempted copy of the left. Alternatively the central column was originally designed as two columns which had to be joined together to hide damage.

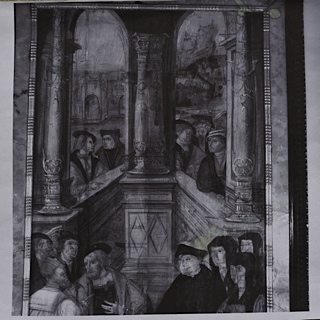

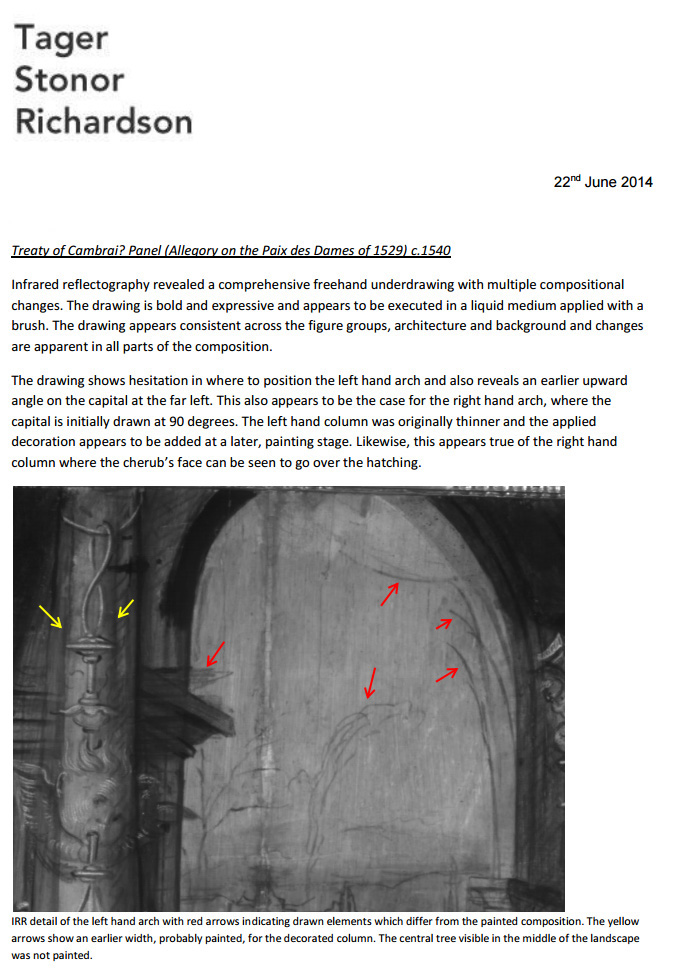

Infrared Reflectography is a research method allowing penetration of paint layers which in the right circumstances can make a design or sketch on the ground layer visible. This so-called underdrawing is the first layout of a composition on the preparation layer of a panel or canvas that is subsequently executed in paint. Examination with in IR can give us an impression of this stage in the creative process which is normally hidden beneath the paint surface this technique can also reveal changes in the paint layers themselves. Additionally it will show where the artist has not followed the original outline of whoever did the preliminary sketch. The Painting's underdrawings were exposed and examined by Tager Stonor and Richardson and the photograph here gives an overall impression of that work. Many changes are evident. Two are worth looking at in more detail. First the central pillar has clearly been unevenly treated with the right side showing a dark shadow the whole way down the painting second the cleric's head has had to be redrawn. Originally he was looking down but in the final composition his head has been raised and he is looking much sterner than he did before whether this is because somebody said that he needs to be more commanding or because the ladies to his right were changed and moved and his head had to be altered to make more room is not known.

The yellow arrows shown above show an earlier width, probably painted, for the decorated columns.

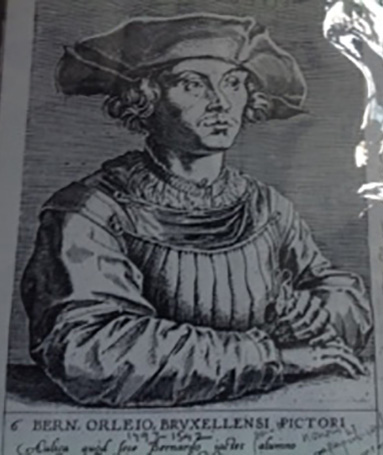

The Bourgognes

I had some difficulty in identifying the two figures behind Charles and Francis. It wasn't until I chanced on the Receuil d'Arras in the Victoria and Albert art library that their identities could be established. They were among portraits by Jacques Leboucq of many eminent and interesting people who were living in France in the early 16th century.

Why are they in the painting? The only clue that I found was in a book published in Geneva in 1548 by Jean Calvin which claimed that they were childhood friends of Charles. Then there is a wildly obscure footnote in a reference book by A.Dek saying that Charles Bourgogne had undertaken a special mission for the Emperor to a court of Arbitration in Cracow. Further research has proved fruitless.

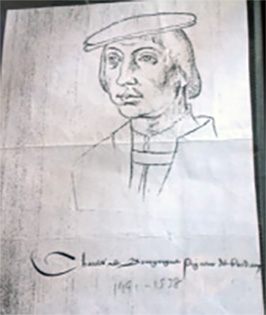

The Best Portrait

The best portrait in the painting is that of the character next to the right hand pillar with one hand on the ledge. Early on I identified him as Oronce Fine, a mathematical professor but somebody pointed out that mathematical professors did not wear red berries. Then I found a print of Barend van Orley.

This was the best identification yet. He was also mentioned in the Sotheby's 1979 sale of the painting which was attributed to 'circle of Barend van Orley'. He is painted in the position that artists putting themselves in their own painting are said to favour. But the painting is obviously not by him although he was at one time Marguerite of Austria's court painter. It is quite possible that it was painted by members of his studio or apprentices who were recording an important event at somebody's request. Occasionally other members of the studio more specialised or skilled might contribute to the painting. It is quite clear that whoever painted the pillars did not paint the background rocks or the scroll.

Jean de Carondolet and The Dauphin Francis

Turning now to the two figures in the left-hand arch. Who are they? Clearly the hand on the shoulder is meant to indicate a warning. It was only after I had had the painting cleaned that the gold embroidered right-hand sleeve of the younger character was revealed. Was it possible that the artist was trying to show Francis I's younger son,also called Francis who had been imprisoned in Spain to allow his father's release? In which case it is likely that the figure stretching out his hand in avuncular style is Bishop Carondelet who had been Francis I's Secretary for many years. Behind them in what looks like the arch of a ruined church is a pikeman walking across the arch. Might he be meant to symbolise the imprisonment of the young Francis in Spain with in fact his brother who isn't in the painting.

Bishop Carondelet or Chancellor Duprat

The commentary describing the painting in the catalogue for the quincentenary Charles V exhibition identifies the cleric in black as Bishop Carondelet. But a contemporary account by J.Thibault describing the peace negotiations and the service in Cambrai cathedral a few days later, identifies the cleric differently as Chancellor Duprat Cardinal Archbishop of Sens and Chancellor of France who was Louise of Savoy's Chief Minister during the captivity of Francis I in Spain.

Whoever it is the Underdrawings (of which more later) reveal that the artist first of all drew the cleric's head slightly downwards but in the finished painting the head has been raised and the bishop' s countenance made to look stern and directly at the disputants. It is possible that the cleric commissioned the painting and disliked the first attempt at portraying himself.

Just under the scroll there dangles a seal, oblate in shape and black in outline with a red Crozier painted inside it. Seals, of course authenticate the documents such as Treaties or marriages to which they are attached and oblate seals signify that they either belong to a lady or come from a religious source- in this case perhaps conveniently both. The Crozier denotes a bishop and of course strengthens the identification of Carondolet. But I was firmly told by one expert that it was ridiculous to suggest that a peace treaty would be identified by such a pathetic looking scroll.

The Obscured figures

Of the 15 people in the painting two are difficult to see and identify because their faces are not fully painted. One wearing a red hat is just beneath the left-hand pillar and sandwiched between the two heads in front of him. The other, slightly more visible, is standing against the right-hand pillar with a slanted red hat and sporting a curly moustache.

I wondered if their faces were fully painted would they be more recognizable. Fortunately I knew someone who specialised in quick drawings of people and asked him to imagine their full faces and see what he could do. The result is shown here.

I have shown the drawings of these obscured faces to a number of people in the hope that they might be identified but so far no luck.

Who painted the painting?

Despite meticulous searching there is no sign of a signature or initials on the painting. The picture was catalogued in 1934 as Westfälischer oder Niederdeutsche Meister. Experts consulted were nonplussed or offered different opinions. Perhaps the most comprehensive view came from a German museum director and it is worth quoting it in translation at some length.

'There can be no question of a work from Augsburg or South Germany. Even if some details of the representation of the figures point towards South Germany, they belong to the universal treasure of the time. It is the time in which German painting took positive cognisance of the Renaissance, and painters used all kinds of moveable scenery. The positioning as well as the clothing and mannerisms of the figures speak a Renaissance language, even if, especially in the visual presentation and also in the right hand group of nuns, late Gothic traits remain relevant. We find just such an intermediate position between modernity and tradition in the panel paintings of the lower and middle Rhine. This eliminates Cologne painting, because that school was under the influence of Bartholomew Bruyn the Elder, whose circle has nothing to do with this picture. I am rather of the opinion that in this case a painter has worked as a compiler that is, he has compressed a triptych form into a 'modern' single picture, that he mixes late Gothic knowledge with Renaissance motifs; that in the depiction of architecture he also proceeds very derivatively, that he knows and selects figures from other associations, and that in the portrayal of landscape he also orientates himself from various models- for instance, Dutch painting. The depiction of the Bower of Justice occurs more commonly in Dutch and Lower Rhine painting.'

If no clue can be found on the surface of early old master paintings, investigation has increasingly focussed on the paintings' underdrawings revealed by means of Infrared Reflectography. This is a research method allowing optical penetration of paint layers which in the right circumstances can make a design or sketch on the ground layer visible. This Underdrawing is the first layout of a composition on the preparation layer of a panel or canvas that is subsequently executed in paint. Examination with IR can give an impression of this stage in the creative process which is normally hidden beneath the paint surface. It will also show where the artist has not followed the original outline of whoever did the original sketch. Additionally it can assist in establishing who the painter/s was by allowing comparisons with other underdrawings where the painter is known.

In the hope therefore that something positive might develop from such comparisons, I asked Tager, Stonor and Richardson to expose and and examine the painting's underdrawings (see Infared Reflectogram). In their 17 page report the first page of which is shown here the authors point to the many differences between the drawn and painted appearances of the painting. To mention but a few,

1. Charles V has been shortened so that he is lower in the painting than Francis I.

2. The lady holding the rosary has also been shortened to allow a third lady some head room.

3. At the drawn stage there was no hole in the rocks.

4. Many hats have been slightly raised.

5. There is no underdrawing under the scroll, possibly suggesting that it was a later addition to the painting.

6. Charles V's cloak was originally drawn at full length but painted so as to show his garter.

Two such changes are worth looking at in more detail. First the central pillar (see infrared reflectograms and colour photos) has clearly been unevenly treated with the right side showing a dark shadow the whole way down the painting. Second the cleric's head has had to be altered. Originally he was looking down but in the final composition his head has been repositioned and he is looking much sterner than he did before. Whether this is because somebody said that he needed to be more commanding or because the ladies to his right were changed and moved and his head had to be altered to make more room is not known.

Eventually I had to realise that studying all the changes between the drawing and painting stages wasn't helping in finding the painter. Only by sending the TSR report to an organisation which specialises in making comparisons between different underdrawings could any progress be made. The trouble here is that such organisations are rare and expensive but I have little doubt that the underdrawings exposed by the TSR report are robust and distinctive enough to make comparisons feasible.

Courtauld Institute Report

To complement the TSR Report, it was suggested that the painting should be X-rayed. I accordingly sent the Courtauld Institute some medical X-rays taken shortly after the painting was bought and the result of their study is available as a PDF report here. The main conclusion is that the middle column was originally two wings of a triptych subsequently joined together.

Infrared Reflectogram

Symbols and Symbolism

With the painter unknown, how else I wondered would it be possible to discover the artist. Perhaps certain striking features of the painting might be found in other similar paintings and a tentative attribution made possible. What are the striking features of The Painting? There are several in no particular order of importance. The shape of the painting, the pillars, the many figures in a small space with 6 on the outside and seemingly indifferent to the 9 on the inside of the pillars, the strange background with an amphitheatre perched on a huge rock and the many symbols.

Fortunately several authors have studied symbols in old masters so that it is fairly easy to interpret them. I checked out the significance of the winds, pillars, rocks, rivers, trees, arches, scrolls, ruins, rosaries, gardens and churches old and new but I failed to notice the octagon with Charles' leg blocking Francis's way. Eight is the number of regeneration, renewal, rebirth and transition. Thus the man standing in the octagon must be or the painter wished him to be seen experiencing a sense of regeneration and renewal. Others had looked at the square floor patterning which is often found in such paintings and commented that it would repeat itself and left it at that.

All these symbols are to be found in many 16th century paintings and it would be impossible to link up The Painting with any of them on account of its symbols alone but that does not lessen the of significance of the octagon and its message.

Bishop Erard de la Marck

Quite why some figures are 'outside' the immediate action and apparently not very interested in it I can't explain but I found several other contemporary paintings that used that approach. The four figures in the right hand arch are identifiable as clearly the artist/s intended they should be. With no other lead I studied a large number of 16th century painters photographs of whose paintings can be found in the Witt collection in London. Amongst them I chanced on someone who seemed like the character with a triangular hat. His name was Bishop Erard de la Marck.

He was the Prince Bishop of Liege from 1506 to 1538 and was made a cardinal in 1520. He had allied himself with Charles V and is recorded in contemporary accounts of the Peace of Cambrai as being present at that event.

Anne de Montmorency

Another difficult identification is the character to the right of Bishop Marck. It is possible that he is Anne de Montmorency Marshall and Constable of France. A soldier statesman and diplomat in the service of Francis I with whom he shared captivity in Spain. Later he helped negotiate the Peace of Cambrai at which he was present.

The Pillars and the Amphitheatre

Another rather wild idea I had to find the painter was to focus on two particular features of the painting - the pillars and the amphitheatre. The pillars stood out because they have been so expertly painted with hobgoblins, winds and cherubs and they have a special link to Charles V whose impresa had two pillars and a motto-plus ultra(further beyond) indicating a gateway onwards. I was intrigued by the amphitheatre because of the sheer bizarreness of having an amphitheatre perched on the top of a large rock with a hole in it.

There was no problem about finding contemporary paintings with pillars but it was harder to locate paintings with amphitheatres in them.

Although it was interesting to examine these two features sadly they did not yield any clues about the panel's painter.

Go to next section: Where has the painting been since the early 16th century? (Provenance)

The Lepke Auction

The fragment and stamps on the back of the panel have long called for follow-up but it wasn't until the painting was prepared for its trip to Ghent in 2000 (where it was to be included in the Quincentenary Charles V exhibition) that something became possible. A restorer steamed the fragment off the back of the panel so that it could be placed in a plastic sleeve and attached to the back of the panel. What I did not expect and should have was that the other side of the fragment was also printed. It read

Photo of fragment about Calraet's flowerpiece

I did not recognise Calraet but found photographs of his paintings at the Witt in London. I was fortunate. One of his boxes contained the relevant photo of the Calraet Flowerpiece with a matching typeface to the fragment's and printed on it the name of an auction house 'Lepke'. At the Victoria and Albert art library where past auction catalogues are kept I asked for all the old Lepke catalogues between 1926 and 1940.

Insert photo of the Lepke catalogue

eI quite soon found the entry for Calraet with my painting's entry on the other side.

Insert photo of the full description of the painting from Lepke catalogue

Both paintings featured in the December 1934 Lepke old master sale in Berlin. But although that was satisfying detective work it led almost nowhere since the auction house appears to have ceased trading in 1940 with all its records probably destroyed.

The Dress

I would expect anyone who wanted to challenge the Ghent catalogue description of the painting as The Peace of Cambrai would question whether the clothes being worn by the 15 figures were authentic to the first half of the 16th century. In fact there was very little dissent then or subsequently about the clothing's fitness to the period as what is being worn belongs to a sartorial style common throughout Europe in the first half of the 16th century. If anything the clothing is puzzling and raises several questions which are worth mentioning here.

1. What is the significance of the various hats being worn, a few red including Charles V's but mostly black?

2. Why are these hats half raised when one would expect them to be fully raised in the presence of royalty.

3. Am I right in supposing that the gold embroidery in the right arm of the character in the left arch indicates royalty, in this case the Dauphin son of Francis I.

4. Why has the artist/s painted the red cloak so as to reveal the garter worn by the figure in red unless it is to help identify Charles V. (Henry VIII had awarded Charles the Order of the Garter). I suspect that Charles is also wearing the Garter Surcoat.

5. What is the significance of the cowls or hoods worn by the three women? They are extraordinary with their 'tails' falling beneath their waists. I searched more diligently for them than any other item of clothing including Pierre Helyot's massive book on clerical dress but I never found them.

Conclusion

To bring the picture's saga up to date it is necessary to mention again that the painting was sold by Sotheby's on Dec 13 1978 as circle of Barend Van Orley. Sotheby's explained that 'circle of' meant that the painting in their opinion is work by an as yet unidentified but distinct hand closely associated with the named artist but not necessarily his pupil. I endeavoured to find out who the seller and buyer were but Sotheby's refused to tell me. Apparently the buyer came under financial pressure and that was why he passed the painting to the owner of the furniture shop to sell for him. As I said at the beginning of this website it looked lonely amongst all the oak furniture and my luck was in.

Anyone who has a U M U U old master painting and would like me to examine it, feel free to see what I can do. Contact me at oldmasterdetective@gmail.com if you'd like to converse over email or to receive my phone number.

Comment facility coming soon...

Please submit your comments below...

© 2021-22 · Website created Summer 2016. All paintings and illustrations owned by their respective authors and factual inaccuracies the sole responsibility of the website owner.

View sitemap · Web Design by Dream Digital